The first edition of D&D conjured magic from a mess, and changed gaming forever

What if I told you that D&D started as a supplement for another game entirely?

Dungeons & Dragons is such a presence on our bookshelves, in our cinemas and podcasts, and on Twitch and YouTube through the likes of Dimension 20 and Critical Role, that it’s hard to believe D&D is a mighty 50 years old.

One explanation for Dungeons & Dragons' longevity is that the RPG isn’t really a single game; it’s a sprawling collection of rules, mechanics, and stories that have evolved so thoroughly over the past five decades that the original edition would be almost unrecognizable to those playing today, even if a number of core aspects of the game still persist, alongside its iconic name. But what if I told you that D&D itself initially started as a supplement for another game entirely?

"Improv, math, and softcore gambling"

Back in 1971, wargaming hobbyists Gary Gygax and Jeff Perren released Chainmail – a medieval-themed strategy wargame using miniatures to represent military units on a map, as you find with Warhammer today. It was heavily inspired by the existing medieval wargame Siege of Bodenburg, but with a 14-page fantasy supplement that let elves, wizards, and dragons rub shoulders with medieval soldiers.

Gygax reportedly discovered the potential for such a mash-up in his weekly wargaming club, when he "turned a plastic dinosaur into a dragon and mixed in wizards and trolls among the men-at-arms." But while Chainmail went through several iterations, its main legacy is how it laid the groundwork for Dungeons & Dragons, launched in 1974 as the debut product of Gygax and co-founder Dave Arneson’s gaming company TSR (Tactical Studies Rules). The game, however, assumed players already owned Chainmail, as well as one of the then-best board games for exploration and adventure, called Outdoor Survival.

As you can see, D&D’s three pillars of combat, roleplay, and exploration were already coming into focus.

In the here and now, the game is getting a major shakeup with the 2024 core rulebooks. However, Dungeons & Dragons' creative director assures fans that D&D "didn't burn the game down" for the new rulebooks: it's still the RPG you love.

Players chose one of three character classes, which became the archetypes for most classes that followed. There was the 'Fighting-Man,' a weapons-user good for combat and not much else; the 'Magic-User,' a low-health, armor-free wizard with access to powerful spells; and an in-between class 'Cleric' that offered a little of both. You could play as a human, elf, dwarf, or Tolkienesque hobbit. This initial version also laid out the basic idea of a moral alignment, with players choosing to be lawful, neutral, or chaotic. That affected their choices and risk aversion in the game.

Crucially, players rolled to determine their ability scores – still Strength, Intelligence, Wisdom, Constitution, Dexterity, and Charisma – before making a character, and they would calculate these scores in order and be stuck with the result. Rolled low for intelligence? Good luck playing a Magic-User, Greg.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Other core D&D mechanics like Armor Class (the number rolled to hit something) and classic spells (Light, Detect Magic, Charm Person) from that initial 1974 document will still be recognisable to many playing Fifth Edition today, as well as the 'Vancian' magic system based on Jack Vance’s Dying Earth novels, in which spells were carefully memorized and then forgotten after casting, ensuring some level of resource-management for reality-bending abilities.

Ambitious but unpolished

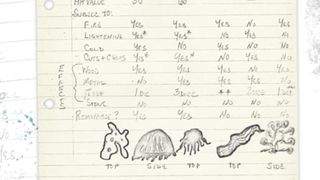

What wouldn’t be recognisable is the game’s mess of terminology, with unclear rules around turns, movement, calculating probabilities, and how different mechanics intersected – making the act of playing the game one of heavy interpretation and educated guesses. I’m partial to the endearing assessment of the 1974 rulebooks by game master and author Justin Alexander: "It’s as if someone took the rules for a dozen different variants of chess, tossed them in a blender, and published the result."

Despite some copyright worries and unpolished materials, the first edition of Dungeons & Dragons achieved an incredible feat: mixing up wargame mechanics with character roleplay and fantasy tropes in order to transport players into memorable stories, embodying a single hero in dungeons full of arcane traps, treasures, and monsters instead of presiding over a historically-accurate battlefield as a tactical commander in charge of many different troops.

However, it’s also a chaotic mix, and its early days were marked by two competing impulses in directing the shape of the game: expansion and concision.

The latest core rulebooks have taken me by surprise. Forget classes, my favorite thing about the new D&D Player's Handbook is its art...

On the one hand, Gygax was keen to add more mechanics, tables, classes, and situation-specific rules that hadn’t been covered in the initial release. Follow-up supplements added the sneaky, trap-picking 'Thief' class (now known as the Rogue) and the holy knight Paladin alongside the Assassin, Monk, Druid, and Ranger, as well as other supplements covering demonic enemies, pantheons of gods, more monsters, and specific rules for using miniatures.

These extensive errata and extensions were brought together in a single edition called Advanced D&D. This was the 'serious,' technical version of the game, and it introduced a host of specifications for each spell being cast, including required components and specific duration and casting times, alongside plenty more numerical tables. When you see the term '1E,' meaning First Edition, this is what that refers to – like a formal launch after a game’s messy beta test.

But there was a simultaneous push towards simplifying the product rather than increasing its complexity. In the same year, TSR also released the Basic Set, a streamlined 50-page D&D system that focused on drawing in players who weren’t familiar with traditional wargaming.

This edition catered to the first three levels of play, and acted as an introduction to AD&D’s more complex mechanics, broadly encompassing the original ruleset and Greyhawk supplement with a few quirks – including a rework of races so that elves, dwarves, and halflings were actually classes with their own designated abilities (the elf being a mix of Fighter and Magic-User), simplifying choices a little.

The Basic Set got revised again in 1981, and in 1983 by game designer Frank Mentzer, who created successive rulesets throughout the ‘80s for higher-level play – up to Level 36, at which point the players are essentially gods. The 'Companion' set specifically introduced the idea of classes you could only choose at high levels, something that returned in Third Edition’s Prestige Classes.

In other words, the early editions of D&D were a potent mix of conflicting and complementary systems, blending together communal roleplay and improv with the rule-heavy wargaming tradition to create something both messy and magical.

But by the end of the '80s, even the ostensibly simpler version of the game had spiraled into a vast collection of rulesets, alongside the Advanced D&D line – and it soon became clear that one of them would have to give.

This is the first article in our five-part celebration of Dungeons & Dragons. Check back next week for our overview of Advanced D&D 2E (Second Edition) and the development of D&D throughout the '90s.

Henry St Leger is a freelance write who has written for sites including NBC News, The Times, Little White Lies, and Edge Magazine, alongside GamesRadar. Henry is a former staffer at our sister site TechRadar too, where started out as Home Technology Writer before moving up to Home Cinema Editor. Before he left to go full-time freelancer, he was News and Features Editor reporting on TVs, projectors, smart speakers and other technology.

Most Popular